2026: THE YEAR OF ITZHAK MAVASHEV

Tavriz Aronova

Memorial

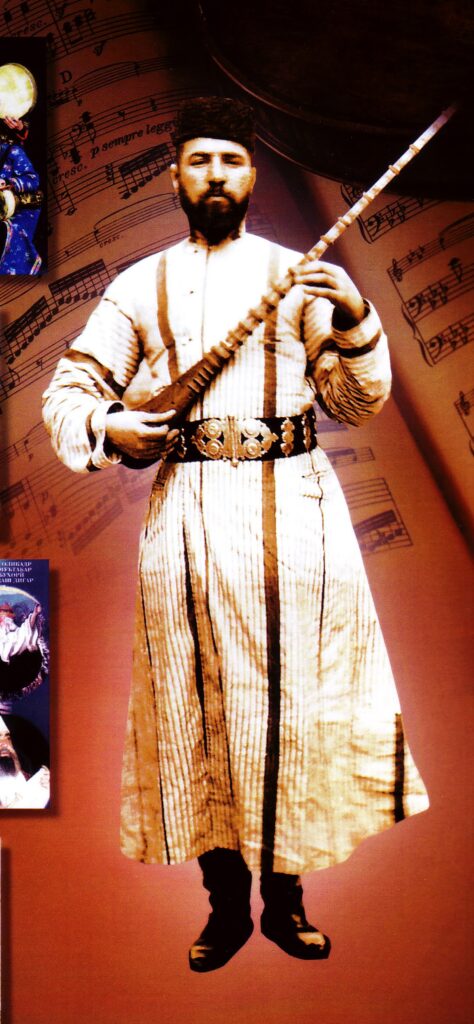

On November 25, 2025, we marked the 120th anniversary of the birth of Itzhak Mavashev — a legendary figure whose name is forever inscribed in the history of Bukharian Jewish culture and in the memory of all who cherish the language, music, traditions, and spirit of our people.

The editorial board of The Bukharian Times proclaims the year 2026 (5786) as The Year of Itzhak Mavashev, as an expression of deep gratitude and recognition for his priceless and immeasurable contribution to our culture, history, and literature.

Itzhak Mavashev was one of the most influential thinkers and educators of Bukharian Jewry in the 20th century: a scholar, translator, folklorist, linguist, and teacher. But above all, he was a bridge-builder who connected worlds that often seem opposed: science and faith, tradition and modernity, Eastern poetry and Western literature, philosophy and folklore. This year marks what would have been his 120th birthday, honoring his impact and the legacy he left in preserving the heritage of the Bukharian Jewish community.

Mavashev’s life was defined by what he built, preserved, and inspired as well as the bridge he created between past and present. In a world where so many young people ask, Who am I? Where do my roots lead? Why does culture and memory matter? His life offers answers that remain profoundly relevant today.

To give readers a firsthand view of Itzhak Mavashev’s life, legacy, and philosophy, we spoke with his son, David Mavashev. In the following conversation, David reconstructs his father’s journey from his early years in Samarkand to his scholarly and cultural work in Central Asia, and finally to his leadership in the Bukharian Jewish community in Israel. Through his recollections, we see Itzhak Mavashev as a towering intellectual whose wisdom, courage, integrity, and devotion shaped generations.

Tavriz Aronova: David, thank you for the opportunity to speak about your father, Itzhak Mavashev. His name occupies a special place in the history of Bukharian Jews of the 20th century: a teacher, folklorist, philologist, thinker, connoisseur of Persian poetry, researcher of language and culture. But his life is so layered that most people know only fragments of it. Today, I would like to restore the full canvas of his life — especially since this year marks the 120th anniversary of his birth, a date that invites a profound reflection on his path.

David Mavashev: Thank you. For me, this interview is not just a biographical account. It is my duty to honor the memory of a man who was not only a father to us but a teacher in the deepest sense. He shaped my understanding of honesty, justice, and hard work; taught me to face difficulties with dignity. He showed that serving one’s people and culture is not an obligation or a choice, but an inner calling. I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to speak about him today, in the year of his 120th anniversary.

T.A.: Let’s begin with his family. What was the environment in which your father was born?

D.M.: My father was born in 1905 in Samarkand, in a family belonging to two outstanding Bukharian Jewish lineages. On his father’s side — the ancient and respected Mavashev family, known for its high level of education and religious authority.

On his mother Sarah’s side — the equally renowned Mulla-Niyoz Pinkasov family from Bukhara, direct descendants of Hakham Yosef Maman Maaravi, the Moroccan rabbi who, at the end of the 18th century, reformed the religious life of Bukharian Jews, introduced systematic education, Sephardic liturgy, and became a central figure of the community’s spiritual revival.

For our family this was not just ancestral lore — it was a deep sense of historical roots and continuity.

My father grew up in an environment where religious learning, culture, poetry, and music were natural parts of daily life. Even in his youth, he stood out for his phenomenal memory, love of reading, and deep interest in texts.

T.A.: You mentioned that your father received exceptionally high-level religious education?

D.M.: Yes. He studied under many Bukharian rabbis. One of them was Yosefi Talmudi. At 17, he received semikha — rabbinic ordination — from the renowned Chabad rabbi Shlomo-Leib Elezerov, head of the Bukharian Chassidim in Samarkand. This was recognition of his exceptional knowledge of Halakha, Tanakh, the fundamentals of the Talmud, and Sephardic liturgy.

Rabbi Elezerov, understanding his potential, gave him a shechita knife, which my father cherished all his life. Later he was forced to sell it to pay for travel to Tashkent and his studies — a symbol of a generation in which faith and education were inseparable.

Father always said: “Faith and knowledge do not contradict each other. They complement each other like day and night.”

T.A.: How did he end up at [the Soviet-era educational institute] INPROS?

D.M.: In 1922, he went to Tashkent and entered Jewish INPROS — the Institute of Enlightenment, founded to create a new Jewish intelligentsia of Central Asia. It was a unique institution, with mostly Ashkenazi professors—philologists, historians, educators.

My father was an honors student. His defining traits were incredible work ethic and discipline. At the same time, he was one of the few who continued to secretly observe tradition. He prayed at night, so no one would see him. This was the era of militant state atheism.

T.A.: You mentioned a serious conflict with the authorities?

D.M.: Yes. It began when my father traveled to Samarkand for a few days and visited a synagogue—he longed to pray in a real communal setting. Someone recognized him and reported it to INPROS.

He was summoned to a Komsomol [a youth division of the Communist Party] meeting where they attempted to expel him both from the institute and the Komsomol—essentially a “wolf ticket,” a ban on any official career.

But what happened next he remembered as a miracle of human solidarity.

The best students rose to defend him. Rahmin Elezerov threw his party card on the table and said: “If you expel Itzhak for praying, I have no place in the party!”

It required enormous courage. The commission backed down. My father continued his studies, though he was expelled from the Komsomol.

He said: “I was happy that I did not sell my conscience for a future position.”

T.A.: Your father had two [university degrees]?

D.M.: Yes. His thirst for knowledge was truly encyclopedic.

First, he completed the biochemistry faculty, studying evolution, anatomy, physiology. He said biology strengthened his faith rather than weakened it. Later, he earned a second degree — in philology. He studied under academician Yevgeny Eduardovich Bertels, one of the authors of the Literary Encyclopedia and the first edition of the Encyclopedia of Islam.

There he studied Tajik literature, Persian poetry history of language, Eastern classics, grammar and morphology.

This became the foundation of his scholarly work.

T.A.: Where did he work in the 1930s?

D.M.: He taught at the Tajik INPROS and at SAGU — the Central Asian State University in Tashkent. Later, in the Agricultural Institute in Dushanbe, he became head of the Department of Western Literature and received the title of Associate Professor.

At the same time, he collaborated with the Irfon publishing house, translated textbooks, and wrote textbooks on Tajik literature, anthologies, teaching manuals, translations in biology, anatomy, physics, chemistry, botany, philosophical and political texts.

He was among those who helped form Tajik scientific terminology.

T.A.: You mentioned a serious conflict with the authorities?

D.M.: Yes. It began when my father traveled to Samarkand for a few days and visited a synagogue — he longed to pray in a real communal setting. Someone recognized him and reported it to INPROS.

He was summoned to a Komsomol meeting where they attempted to expel him both from the institute and the Komsomol — essentially a “wolf ticket,” a ban on any official career.

But what happened next he remembered as a miracle of human solidarity.

The best students rose to defend him. Rahmin Elezerov threw his party card on the table and said: “If you expel Itzhak for praying, I have no place in the party!”

It required enormous courage. The commission backed down. My father continued his studies, though he was expelled from the Komsomol.

He said: “I was happy that I did not sell my conscience for a future position.”

T.A.: You mentioned important publications that received wide recognition.

D.M.: Yes. In 1959–1960 he published two major articles: one on Levicha Bobokhanov — one of the great masters of Bukharian Shashmaqom of the early 20th century — and another on the works of Shokhini Sherozi, the great 14th-century poet who laid the foundation of Jewish poetry in the Persian language.

Both articles appeared thanks to the support of editor-in-chief Pulod Tolis, a talented journalist and intellectual. Sadly, Tolis was later dismissed, fell into despair, and took his own life — a tragedy for the entire intelligentsia of Dushanbe.

T.A.: How did your father gain such deep understanding of Shashmaqom?

D.M.: He loved Shashmaqom since childhood in Samarkand. He knew legendary masters such as Levicha Bobokhanov, Ota Jalol Nasyr, Nisim, Mikhoel and Gavriel Mullokandov, the Tolmasov brothers, and Khoja Abdul Aziz Rasulov. Some of them were his lifelong friends.

He had no singing voice, but he knew all the maqoms, their structure, history, and poetic texts. He would say: “Shashmaqom is not music. It is a way of thinking.”

T.A.: His personal life was not easy, correct?

D.M.: Yes. In 1929 he married a talented, beautiful singer, Frida Davydova, in Tashkent. But in 1947 she died suddenly during childbirth, leaving two daughters, Tamara and Natella. It was a heavy blow.

He moved to Stalinabad (Dushanbe) at the end of 1947. In 1950 he married my mother, Tovya Davydovna Khaimova — a strong, energetic, educated woman who had a distinguished career in the Soviet cultural system. They were an exceptionally harmonious couple. They had two sons, me and my younger brother Avner.

T.A.: Your father was one of the first Soviet citizens to visit Israel in 1966. What did this trip mean to him?

D.M.: It was the dream of his life — to visit the Holy Land.

He spent a year there, traveled to religious centers, met rabbis, studied liturgy, collected materials on the history of Bukharian Jews in Israel. He brought materials that helped his cousin, Nisim Tadjir, publish in 1971, shortly before his death, the book Toldot Yehudei Bukhara.

His sister lived in Israel and was married to Nisim Tagger. He also met his cousin Clara Tagger, who lived in Argentina.

This trip gave him a sense of spiritual completion. After returning, he secretly taught Hebrew and encouraged people to emigrate, believing there was no future in the USSR.

T.A.: How did he experience repatriation?

D.M.: It was difficult, but he faced it with dignity. We arrived in Israel in December 1973.

He refused to close himself off in the past. In 1974 he became the editor-in-chief of Hathiya, only the second weekly newspaper in Israel published in Bukharian (in Hebrew script and Cyrillic). In the 1960s, Nisim Tadjir had published the newspaper Tvuna. The journal became a cultural center for Bukharian Jews of that immigration wave.

T.A.: When did his health begin to decline?

D.M.: In mid-1976 he was diagnosed with ALS — Lou Gehrig’s disease. It is a terrible illness. He fought bravely, but it progressed. He became fully paralyzed, yet continued to work and publish the journal until his final days.

He passed away in September 1978… But his influence did not vanish. He left students and followers who revered him as a teacher — “Muallim,” “Ustod,” a mentor.

Among them were poet Mirzo Tursunzade, musicologist Zoya Tajikova, ethnographer Amnun Davydov, Dr. Pinchas Abaev. He supported the young scholar Michael Zand and translated Zand’s book about Omar Khayyam into Tajik (his name was not mentioned — it was simply his help to Zand).

He gave semikha to Rabbi Yushuvakh Muradov, long-time leader of the Jewish community of Dushanbe, and supported the community’s spiritual life.

T.A.: What kind of person was he?

D.M.: A man of light. An erudite, an encyclopedist, a sage. He knew: Torah and Talmud; the history of religions — Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism; Persian poetry; Bukharian Jewish literature and folklore; Greek mythology; Western literature; philosophy; political science; natural sciences.

He tirelessly helped his community with religious rites and traditions. He slaughtered chickens for free, performed chuppahs, conducted mourning ceremonies — and never considered himself “religious.” He simply served people. He was regarded as the community’s rabbi not by title, but by essence.

T.A.: His legacy today?

D.M.: He never sought titles. He said: “I don’t need ranks if the price for them is my conscience.” He wrote two dissertations but refused to defend them because ideological compromises were demanded of him. He never betrayed his morality.

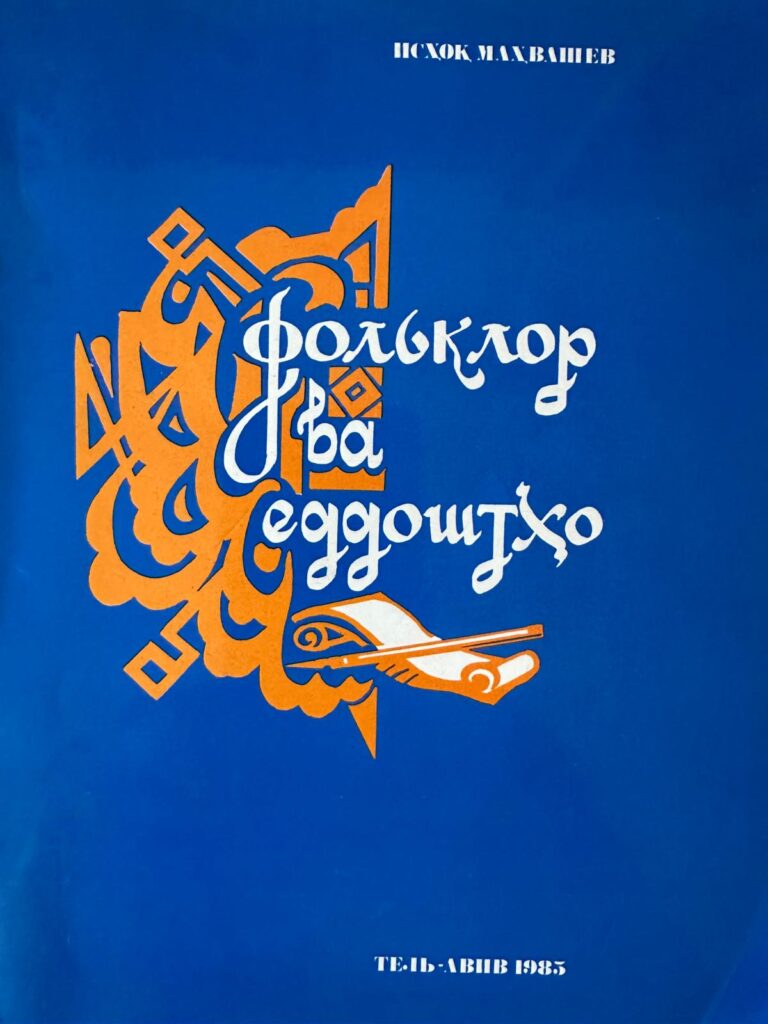

Today his legacy consists of articles; books; translations; the memories of his students; his contributions to Tajik terminology; his research on Shashmaqom; his studies of Persian poetry; his work in Tashkent and Dushanbe; and his service to the community in Israel.

This work continues through the Itzhak Mavashev Foundation—an institute for studying the heritage of Bukharian Jews in the diaspora.

To me he was not only a father and mentor, but also a very close friend—an example of a man who lived honorably, nobly, and never betrayed friends or principles.

T.A.: David, thank you. Your story is not just a biography—it is the history of an entire era.

D.M.: Thank you. If this story helps preserve the memory of our people, then I told it not in vain.

T.A.: This year marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Itzhak Mavashev. How do you perceive this date?

D.M.: For me it is not just a round number—it is a reminder of the scale of his personality. He was born at the dawn of the 20th century, lived through the entire Soviet period, survived repression, war, and emigration, began a new life in Israel—and through it all remained a teacher, an enlightener, a man of profound inner culture.

The 120th anniversary is not only a time to remember, but also to restore his legacy: his articles, translations, textbooks, Shashmaqom notes, studies of Persian poetry and Tajik literature, his role in developing the Tajik language, his work in the institutions of Tashkent and Dushanbe, and his service to the community in Israel.

I hope this anniversary becomes an invitation to rediscover him as a thinker, scholar, poet, educator, and a person of extraordinary spiritual strength.

T.A.: Thank you very much for such a detailed account of your father. I am sure the readers found it fascinating. For me personally, listening to your story brought me to the conclusion that Itzhak Nisimovich Mavashev—a [visionary scholar], endowed with encyclopedic knowledge and profound inner culture—brought honor and glory to our entire Bukharian Jewish people. I hope that you, David, and the editorial board will not limit yourselves to this material, because the figure of I.N. Mavashev is so significant and authoritative that it is worth continuing our conversations about him in the pages of the newspaper.

D.M.: Thank you, Tavriz!