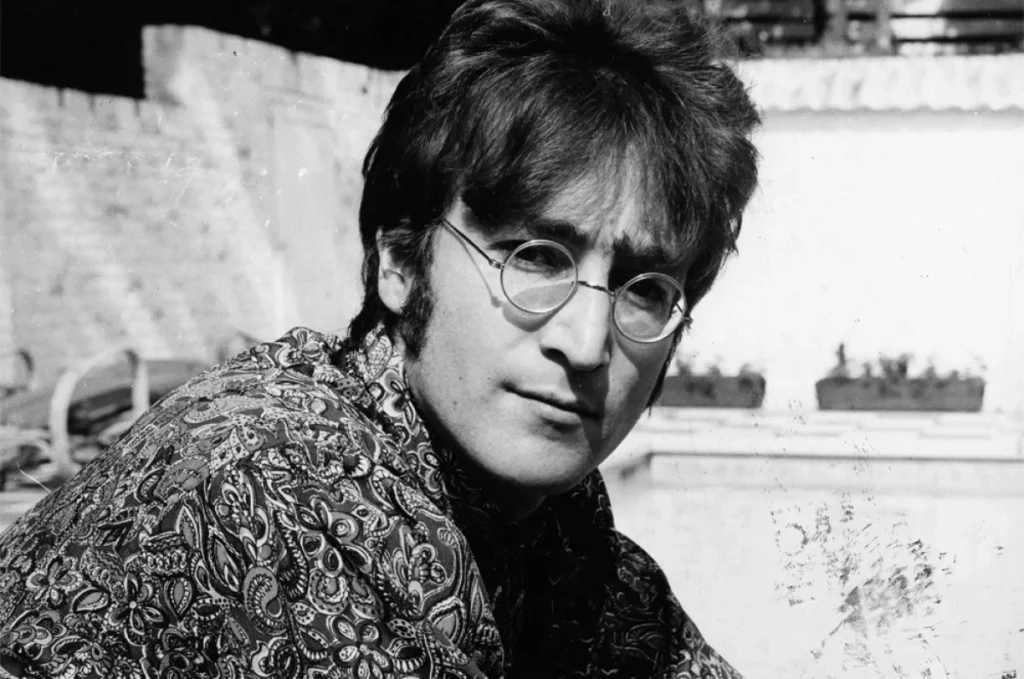

On the 45th anniversary of the assassination of Beatles singer-songwriter John Lennon on December 8, 1980, in New York City, Rafael Nektalov reflects not only on Lennon, but on the wider impact of pop, rock, and jazz music in Soviet society. Growing up in a country saturated with Lenin’s portraits and slogans, it was Western music — with Lennon as one powerful voice among many — that quietly reshaped his understanding of freedom, individuality, and modern culture.

In this exchange with Erin, an American whose hippie father raised her on every Beatles album, they explore how the Beatles and other Western musical movements transcended borders, ideologies, and generations, leaving a lasting imprint even behind the Iron Curtain.

Erin Levi: Rafael, we’re marking 45 years since John Lennon was assassinated. Where were you when you heard the news?

Rafael Nektalov: I was still in Samarkand then, a young man of 24. Where were you?

EL: I wasn’t born yet, but the loss was already part of my family’s story. My parents were vacationing in Caneel Bay, St. John — only three years married — when they learned Lennon had been killed. It was December 9, 1980. My dad had torn his Achilles tendon that summer and was still using a cane, but they’d gone for their first big vacation anyway.

That morning, he was walking slowly on the beach when he saw a man reading a newspaper. It was open so he could see the back page — a huge picture of John Lennon with big letters: “LENNON SHOT.” His heart dropped. It felt like a big part of his life had just been ripped out of him. This was a shot that could be felt around the world — and for generations to come.

My dad was born in 1948 — the same year Israel was founded, actually — and he raised my sister and me on every single Beatles album. My sister is named Julia — my dad always loved that song John wrote about his mom. When my sister was a baby, he made a video of her with the song as the soundtrack.

RN: Julia! What a beautiful connection.

EL: Yes—from birth to death. My dad wants “Here Comes the Sun” to be played at his funeral (which, G-d willing, won’t be for decades to come.) The Beatles are that foundational to our household.

As a kid, my favorite Beatle was Ringo because he starred as a magical conductor in a children’s TV series called Shining Time Station. I was just 5 years old. That was my entry point before I really understood the music.

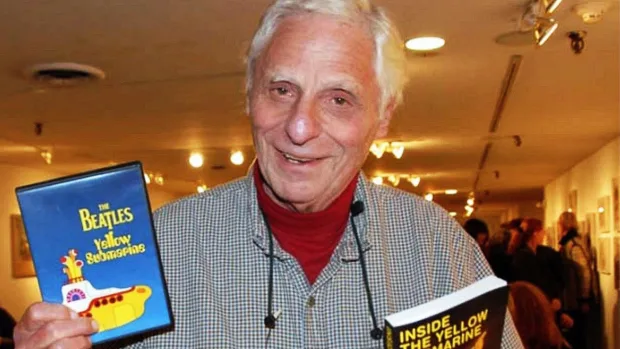

When I was a little older, I remember watching the musical film “The Yellow Submarine” at the home of the man who produced it: Al Brodax. Al was a good friend of my parents who lived in Weston, CT until his death in 2016 (he was 90). He used to share stories of what it was like working with the Beatles. So that became my favorite album for a while. If you haven’t seen the animated film—you should. It’s trippy.

RN: You know, I first heard the Beatles’ songs when I was 13 years old. Born in the years of Khrushchev’s Thaw, in the Jewish mahalla of “Vostok,” three years after Stalin’s death, I grew up and formed my musical tastes during the years of Beatlemania.

EL: It’s remarkable that Beatlemania reached Samarkand. How did you even access their music in the Soviet Union?

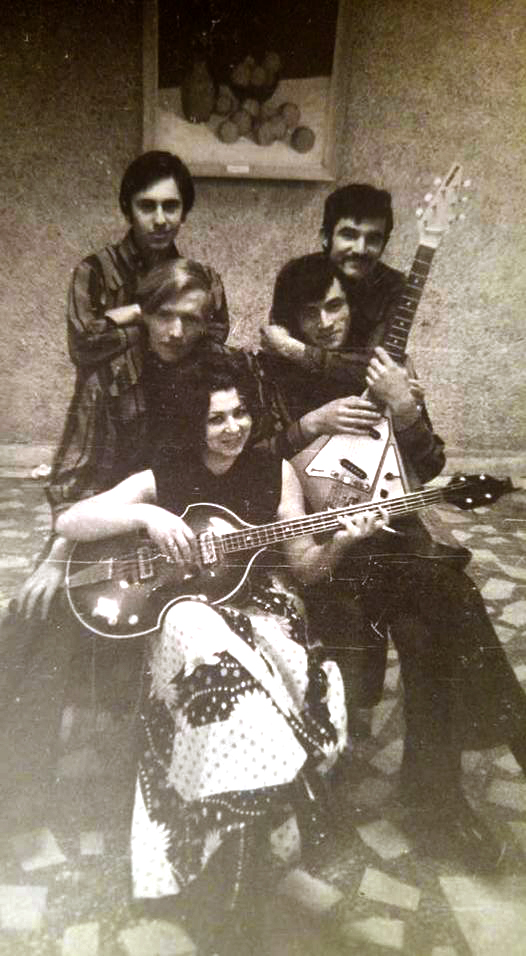

RN: At 14, I played in an ensemble that Avrom Tolmasov, Yasha Yusupov, and I put together at the Palace of Culture No. 7. The first person who taught us how to perform the works of Paul McCartney and John Lennon was our music director, Boris Urilovich Tolmasov, a talented saxophonist from the Dushanbe pop orchestra “Gulshan,” who had just moved to Samarkand.

He taught the young members of the vocal-instrumental ensemble (VIA) how to play pop music, what swing was, and the first chords, which were noticeably different from the canons of classical music. For me, a 7th-grade student at Children’s Music School No. 3, who played classical music on the violin and piano, Boris taught me to play the ionika (electronic organ), and others to play the guitar and drums — the first instrumental melodies that were playing all over the world but were completely unknown to us, raised on examples of Soviet song, popular Azerbaijani, and Armenian lyrical and dance melodies.

EL: So Boris was your gateway to the Beatles. What was the first song you played?

RN: That’s when we first played the Beatles’ hit, “Yesterday,” live. A little later, Boris gave Avrom the album Abbey Road, as well as a large portrait of his idol, Louis Armstrong, the “King of Jazz,” the legendary American trumpeter, singer, and composer.

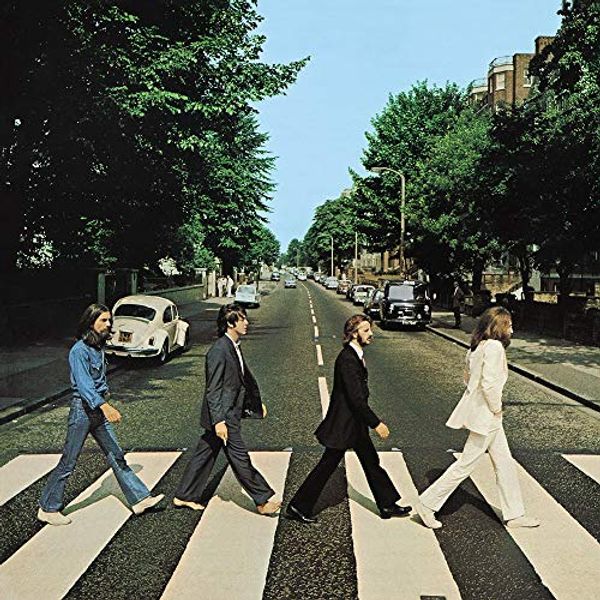

EL: Abbey Road! I remember staying for a couple of weeks at St John’s Wood in London and seeing all the tourists cross that zebra crossing. It’s become such a pilgrimage site.

RN: That iconic album — the entire Vostok neighborhood was proud that we had it. We began to listen intently to the unfamiliar songs, one after another, and I felt a thrill.

Naturally, I didn’t know the names of these compositions then, but the melodies were etched into my mind, as was the name of the group — “The Beatles,” which translated meant “beetles.” This seemed a complete mismatch. We had bands like “Veselye Rebyata” (Merry Fellows), “Golubye Gitary” (Blue Guitars), and the local “Yalla.” But here — “beetles.”

Then, after forming the new ensemble “Orpheus,” the solo songs of John Lennon and Paul McCartney entered my life. Slava Kumanikin sang them for us.

EL: [laughs] ‘Beetles.’ The name does seem strange when you think about it. But they became bigger than their name — at one point, John Lennon famously said the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, which caused a huge controversy.

RN: Yes, I read about that later. The very fact that Avrom and I could listen to the album in 1970 (!) seriously boosted our standing among our peer musicians. While most of the ensemble songs by the Beatles sounded to me from reel-to-reel tapes, I listened to their solo works exclusively on vinyl records.

EL: Vinyl was precious. My dad still has all his original pressings. But I’m curious — how did the Soviet authorities react to the Beatles? It seems like Western rock would have been seen as dangerous.

RN: You’re right to wonder. The first mention of “The Beatles” in the Soviet press dates back to the beginning of 1964. I was 8 years old then and knew nothing about these musicians. Beatlemania, which began in the West in the autumn of 1963, swept across the whole world.

But in the USSR, they immediately understood the need to keep their finger on the pulse and began to create amateur vocal-instrumental ensembles (VIA) with guitars, ionikas, and drum kits at universities, palaces of culture, and factory enterprises. This was our answer to Western rock (The Beatles, Deep Purple, etc.).

EL: So, they co-opted the format rather than banning it outright?

RN: Exactly. VIAs borrowed the instrumentation (guitars, drums) and energy of Western groups but adapted to Soviet ideology, making the lyrics patriotic, lyrical, or folkloric. Hence bands like “Syabry,” “Pesnyary,” “Yalla,” and “Gulshan,” which actively introduced folk instruments and motifs, corresponding to the Soviet idea of “national spirit.”

We, too, introduced the first arrangements of Bukharan Jewish songs into the “Orpheus” ensemble’s repertoire: “Boy-boy,” “Shast-shastuchor,” and “Makhvashi nozuk.” With the latter, we even performed on republican television.

EL: So you were blending traditions. That’s fascinating.

RN: Yes, but we also performed pure Beatles. Subsequently, the Beatles also sounded from Soviet radio receivers and television screens. The instrumentals, cover versions, adaptations, and originals of “The Beatles” were used quite often. One only needs to recall the TV show “Vokrug Smekha” (Around Laughter), where the melody of “All My Loving” was used to accompany a segment.

EL: I sang one of their songs in high school choir — “Imagine.” You may say I’m a dreamer, But I’m not the only one, I hope someday you’ll join us, And the world will be as one. Such a hopeful song, perfect for young idealists setting out into the world…

RN: “Imagine”! That song became everything to me.

When we had the opportunity to perform a solo concert on the stage of the Officers’ House in 1974, we included several songs from The Beatles’ repertoire. I absolutely loved “Imagine” from John Lennon’s album of the same name. It became for me a model of what a modern song should be like. In Imagine, the author laid out his views on what the world should be: without materialism, without state borders, without division into nations and religions.

Imagine there’s no heaven It’s easy, if you try No hell below us, Above us, only sky John Lennon became the Schubert of the 20th century for me.

EL: “The Schubert of the 20th century” — that’s beautiful.

RN: Later, in America, I read that for him, this song “is essentially the Communist Manifesto, although he himself is not a communist and does not belong to any political movement.” The irony wasn’t lost on me — here I was in a communist country, finding freedom in a song that Lennon himself compared to Marx, yet it was about transcending all such divisions.

EL: That’s the power of the Beatles, isn’t it? They mean something different to everyone, across every border. I’ve been in the Himalayas for the last two months, and young people are still inspired by the Fab Four. There’s a Beatles-inspired band called “The Yellow Pencils” in Bhutan — a country that was never colonized — yet the Beatles reached it. Meanwhile in Nepal, a rock musician named Tashi played “Something” at our lodge in Chame, Manang just this week during happy hour.

RN: “Something” — one of George Harrison’s finest. That’s one of the top five favorite songs I perform in piano arrangements, along with “Oh! Darling!” and “Imagine.” I came to love and master them thanks to my teacher, Boris Tolmasov, who is alive and well in Israel.

EL: So many of your musical family ended up scattered across the world.

RN: Yes. With a special fervor of patriotism and love for the Fatherland, we sang songs about never leaving. We even performed a song we called “Perekat-pole” (Tumbleweed), expressing our disagreement with those who left the homeland in the 70s. The lyrics reminded us that every person has only one mother and one Motherland.

Though the Earth is unimaginably vast, On it, in all ages and times A person has only one, one, one mother. And the Motherland—is one!

But this did not save any of us from repatriation and emigration to the West. Over the years, everyone moved away.

Avrom Tolmasov and Olga Bunimovich preserved the memory of the historical homeland. They live in Israel. For others who headed to Europe, America, Canada, and Australia, the homeland remained the place where childhood and youth were spent.

EL: And you ended up in New York.

RN: Yes. And on December 8, 1980, my idol, John Lennon, was killed in New York, where I currently live.

EL: Right. It happened right in the archway of the Dakota Building on the Upper West Side. My parents’ friends live nearby in the San Remo, and I’m always aware of it when I go up there. The Strawberry Fields memorial in Central Park is just across the street.

RN: In Corona, a few stops from my home, there is the Louis Armstrong Museum. Queens is the home of the great American musician, composer, and singer — remember, Boris gave Avrom that portrait of Armstrong along with Abbey Road.

EL: It all connects. Speaking of New York, once when I took the train from Connecticut into Grand Central, I found myself rubbing shoulders with people as I tried to make my way out of the terminal—it was PACKED. I was running late to an event and couldn’t understand why so many people had their phones out and were peeking through the walled off Vanderbilt Hall. I was annoyed. I only found out when I caught the train home that I had just missed one of the greatest surprise concerts ever: Paul McCartney! [laughs]

That said, while Paul is great, you know, he’s an example of one being not as good as the whole. Unlike the USSR, America prizes the individual. But in music, there’s harmony and alchemy achieved from a group. The Beatles together created something none of them could achieve alone. That’s why they remain timeless — arguably the best band in the world. Their music transcends space and time.

Rafael: Indeed. We, the musicians, even tried to look like our idols: long hair, jeans, “Lennon-style glasses,” stage behavior. That iconic Abbey Road vinyl album, which the entire “Vostok” neighborhood was proud of, was once gifted, right before my eyes, by Avrom Tolmasov to a beautiful girl named Nadezhda, with whom he was in love. I didn’t try to talk Avrom out of it; I saw how much she meant to him.

Currently, the album is in Atlanta. But that is another story.

EN: [laughs] Love and vinyl — two things worth sacrificing for.

RN: [laughs] Yes.

I don’t sit down at the piano very often to play my favorite melodies anymore. But when I do, those Beatles songs are always there.

Thank you, Boris Urilovich!

EN: You must play it for me sometime! So I can thank Boris, too!

You know, it’s incredible how the Beatles connected a Jewish boy in Samarkand and a girl from Connecticut — and continue to connect people today.

RN: It’s a story intertwined with history and geography. From Samarkand to New York, from Lenin to Lennon — music found a way.

Erin Levi