For years after the Iranian revolution of 1979, my mother lived under the oppressive rule of the Ayatollah’s regime, stripped of basic personal freedoms and forced to live in constant fear of persecution for being Jewish. In 1986, after multiple arrests in the family and an aggressive altercation with the morality police, she finally fled Iran as a refugee in pursuit of a better life. After years of resettling in the United States, my mother struggled to assimilate, holding on to hope that she might one day return to the land where she took her first steps.

For decades after the revolution, Iranian Jews like my mother, have been in a state of *longing and belonging*–building a new home in a new country while yearning for and holding onto the memories of their diasporic homeland. This sense of nostalgia persisted through my formative years, nurturing an interest that led me to begin a journey for deeper connection to my ancestry. For many years, I had a strong interest in visiting Uzbekistan, not only due to the linguistic and historical connection to the Persian empire but also for the Jewish communities that remain there.

Destination: Uzbekistan

In early September, I turned this interest into a reality with the help of several passionate individuals who share the same love and respect for Jewish communities of the diaspora. My journey was primarily centered around Samarkand and Bukhara, two cities in Uzbekistan with deep ties to the silk road and the larger Persian empire.

In Samarkand, I was connected to Amir Bafoev, a young Bukharian Jew who graciously offered an insider view of Jewish Samarkand. Currently, there is only one active synagogue that supports a community of less than 200 Jews in Samarkand, most of which are from blended families or may have only recently become aware of their Jewish origins.

We began our tour in Samarkand at the demolition site of Or Avner synagogue (also known as the New City Synagogue), established in the early 1900s. The synagogue had so many structural issues that it was demolished last year for redevelopment purposes. A beautiful menorah remained in the demolition site with no clear timeline for if and when the synagogue would be rebuilt, a stark reminder of the dwindling Jewish community.

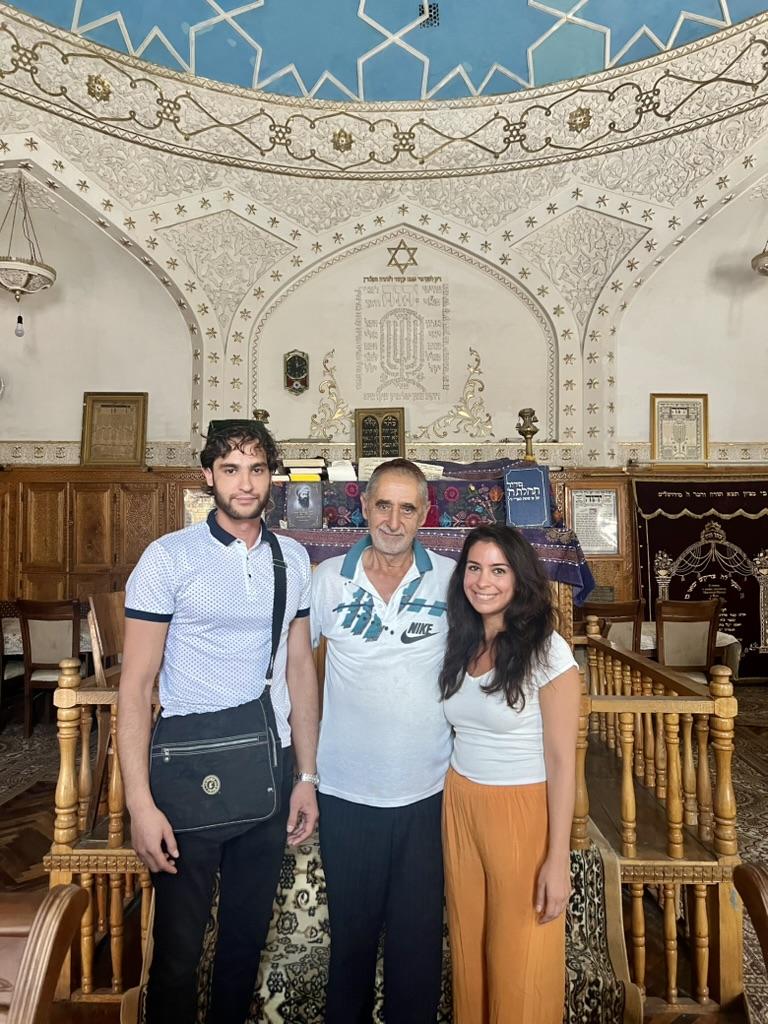

We next journeyed to the *Mahalla* of Samarkand, or Old Jewish Quarter, which was once considered an independent part of the city led by an elected leader or “Kolantar” who managed the affairs of the city up until the time of Soviet restrictions. The most prominent site in this area is the only remaining active synagogue in Samarkand—Gumbaz Synagogue, translated in Bukharian and Farsi to “Synagogue of the Dome” because of its blue dome, a staple of Persian Islamic architecture of the 19th century. The gatekeeper of the synagogue is Yosef, a gabbai (synagogue official) who lives nearby with his wife. All his children have immigrated to Israel, yet he remains in Samarkand as the gatekeeper of the community.

Feeling at Home Speaking Farsi

My encounter with Yosef was the first time I was able to speak Farsi with a member of the Jewish community. Most Bukharian Jews now speak Russian, Uzbek, or Tajik depending on where they live, but the older generation of Bukharian Jews still speak Bukharian, a Judeo-Persian dialect of Tajik and Farsi. Speaking with Yosef in a common mother tongue made me feel at home as he described his love for his home country, bestowed a priestly blessing in the familiar tune spoken by my father, and picked a stem of Persian mint from the synagogue’s garden as a farewell gift.

The final stop in our Samarkand journey was the Jewish Cemetery, just outside of the Jewish Quarter. The cemetery was well-preserved with both old and new graves. This was the first Jewish cemetery I had ever been to with images of the deceased on the tombstones, both a beautiful and somewhat odd tradition adopted from Soviet culture. Walking through the cultural site, I couldn’t help but somberly reflect on how many Jews once lived here and how few remain.

In Bukhara, a few days later, I was connected to Valeriya Kraeva through a contact in Tashkent. Valeriya runs many of the social services for the Jewish community in Bukhara, including interfaith initiatives with the larger Bukharian cultural community. The dwindling Jewish community in Bukhara stands at less than 150 people, although social services have identified several hundred additional individuals that have some Jewish lineage.

Valeriya met us in the historical Jewish Quarter where we began a tour of the Jewish sites. First, she showed us the local Jewish primary and secondary school, both of which welcome Jewish and non-Jewish students and are currently under tight security given the global rise of antisemitism. She mentioned that the schools still teach Hebrew, despite only 10% of students being jewish.

Before leaving the Jewish Quarter, we visited the oldest synagogue in Bukhara, aptly named the Synagogue of Bukhara, first established 400 years ago. The synagogue is run by Abraham Itshakov who maintains the synagogue through donations (often from tourists) and organizes services every Friday night and Saturday morning. In perfect Bukhari, Abraham described the ancient history of the synagogue and the many visitors (including diplomats) over the years. We returned to the synagogue later that day for Friday night services, and I was delighted to see nearly twenty people in attendance, most of which were Bukharians that now live in Israel and are visiting their home country.

We then walked about ten minutes outside of the Jewish Quarter to visit Ohel Itzhak Synagogue, where we planned to have Shabbat dinner later that night with the Rabbi, his brother Rafael Elnatanov, who is the Jewish community chairman, and his family. The synagogue is 225 years old and remains active thanks to Rafael’s community efforts.

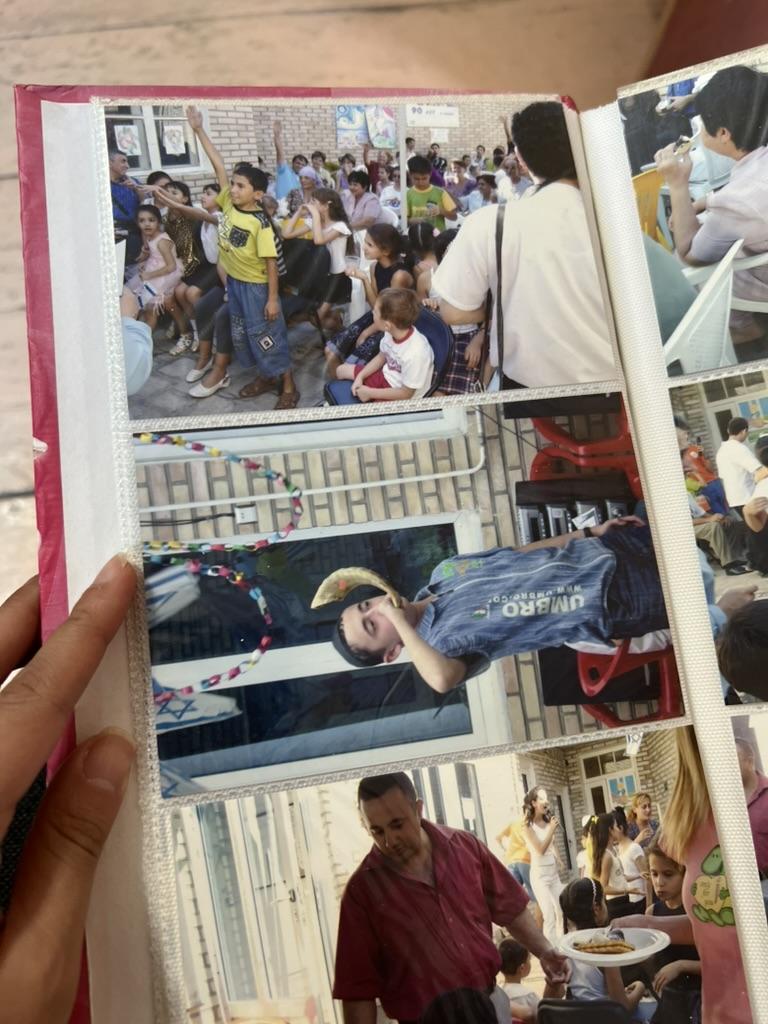

Valeriya also took us to the community’s offices, once funded by the JDC (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee), but now maintained by Valeriya and Rafael. There, she showed us pictures of the community twenty years ago, full of families, arts and crafts, and a bustling community center. Despite the dwindling Jewish population, it was beautiful to see the community’s efforts continue in new and innovative ways, through interfaith dance performances, concerts, and other cultural activities bringing Jewish and non-Jewish families together for dialogue and connection.

We concluded the afternoon by visiting the home of a widowed community member who is supported by the community’s social services. She welcomed us into her traditional Jewish, Bukharian home, ordained in traditional Central Asian motifs and Jewish symbolism.

Across the street, we visited a local couple that sells handmade, traditional Bukharian Jewish garb such as *Joma*, an embroidered ceremonial robe, which is often worn on Jewish holidays and special occasions.

Shabbat in Bukhara

And finally, in the evening, we made our way back to Ohel Itzhak Synagogue for Shabbat dinner. In Bukharian tradition, men and women sat at separate tables. The intimate dinner included myself, my dear friend Erin, who I had been traveling with, the Rabbi, Rafael (chairman of the Jewish community) and his wife Mazal, and their three children. The sweet tune of *Shalom Aleichem* and the Jewish Plov, a green rice pilaf spattered with dill and adapted from the Persian rice dish *Polo Shevet Bagholo*, felt deeply familiar to my own Shabbat customs.

Halfway through the meal, Rafael stood up and gave a small speech about how exciting it was to be joined by visitors and that he would like for me to say a few words. With Valeriya as a translator, I spoke about the intention of my journey to Uzbekistan, my desire to connect to my ancestry, and the feeling of being immersed in a culture so familiar.

In a gesture that felt both unorthodox and welcomed, Rafael pulled a chair to the women’s table, and we began a conversation that lasted for over an hour. We spoke about politics, family, community, and our deep desire to visit Iran, the proverbial source of our mutual ancestry. As the distance between our tables and our homelands seemed to dissolve, I understood, in a more profound way, the *longing and belonging* that had so deeply shaped my mother’s life and my own search for connection. For Jews of the Persian diaspora, their identity remains sacred, deeply rooted in ethnic belonging, a collective consciousness of a unique and soulful culture dating back thousands of years ago.

A few weeks after returning, as I settled back into everyday life and the weeks of High Holidays concluded, I was reminded of the Jewish traditions of *Elul*, the month preceding the holidays. Elul translates to “search,” indicating a time to search our hearts and souls for deeper meaning and personal growth. My “search” this Elul brought me to Uzbekistan.

I believe the journey to understand and connect to where we come from is an important part of deepening our relationship to ourselves, our families, and the Divine. I am immensely grateful to the Bukharian Jewish community for guiding me through my version of this journey and for making it possible through their resilience and commitment to preserving their beautiful culture.