Culture

What does it mean to truly see? In this wide-ranging conversation with Magnum photographer Gueorgui Pinkhassov, conducted in Bhutan by Bukharian Times Editor Erin Levi during the November 2025 royal launch of “Bhutan: Portrait of a Kingdom,” Pinkhassov speaks candidly about photography, while revealing his wish to preserve rare documentation of Bukharian Jewish life in Soviet Central Asia and a vast archive of risky Moscow street photography from the 1970s-90s. The interview underscores the cameraman’s role as a witness to cultures that have dispersed, transformed, or vanished—and the quiet urgency of safeguarding that record.

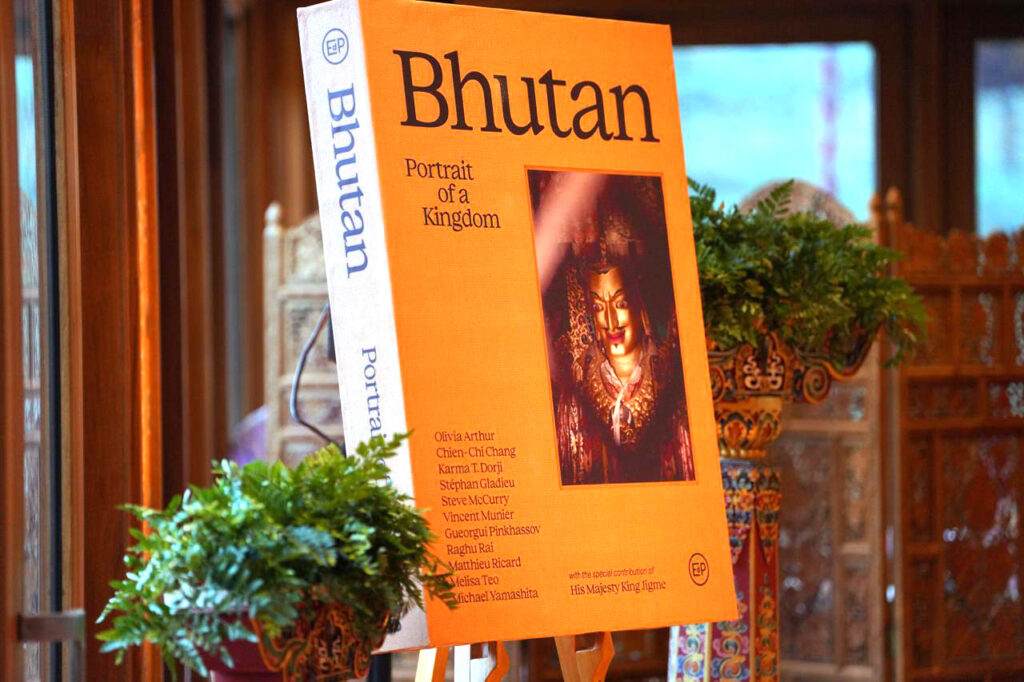

«Two Bukharians in Bhutan!» Rafael Nektalov, The Bukharian Times Editor-in-Chief, texted when he saw my photo with photographer Gueorgui Pinkhassov at Dechencholing Palace in Thimphu for the launch of «Bhutan: Portrait of a Kingdom» (Les Éditions du Pacifique) on November 13, 2025.

The large-format photography book showcases the Land of the Thunder Dragon, a tiny kingdom wedged between India and China, through the lens of ten international photographers, including Steve McCurry, Gueorgui Pinkhassov, and Matthieu Ricard, with contributions from writer Pico Iyer, and Bhutanese photographers Karma T Dorji and King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck.

After three years at The Bukharian Times, I am honored to count as a Bukharian.

Just how did I end up meeting Pinkhassov, a 73-year-old Russian-French photographer with Bukharian ancestry, in Bhutan?

Karma, you could say. Or bashert?

I was in Bhutan on assignment with BBC Travel to interview Prime Minister Dasho Tshering Tobgay for a story on his home region, Haa Valley, when I learned about the book launch. I had already noticed Pinkhassov as a contributor months ago when the tourism board promoted the forthcoming book on social media. Immediately, I sent it to Rafael asking if he knew Pinkhassov and if he was Bukharian, and he said, «yes.»

[In fact, Rafael interviewed Pinkhassov in issue 973 of The Bukharian Times.]

I’ve been a ‘fan’ of Pinkhassov—an esteemed Magnum photographer since 1988 and frequent contributor to The New York Times—for some years. Only since working for The Bukharian Times did I recognize his surname as distinctly Bukharian.

We meet at Brusnika, a Russian café in Thimphu, and order chicken stroganoff and pelmeni overlooking Tashichoedzong, the palatial seat of Bhutan’s Royal government. The plates are nearly clear, but there’s a pickle left and he picks it up.

Gueorgui Pinkhassov may call Paris home since 1985, but his Russian roots run deep. “You remember Gogol’s phrase: ‘What is healthy for a Russian is death for a German.’» He raises the pickle with a smile: «What is healthy for a Russian is death for an American.»

Little does he know that despite my dual American-German citizenship, I’m half Russian-Jewish myself. Bring on the gherkins!

Erin Levi: It’s a pleasure to finally meet you, Gueorgui, and funny that it’s here in Bhutan. Mazel Tov on the book. Tell us about your photographic assignment for Bhutan: Portrait of a Kingdom. What left the strongest impression?

Gueorgui Pinkhassov: In addition to filming the atmosphere of the capital city Thimphu, I was asked to photograph artists and craftsmen. I flew by helicopter to Gasa, a mountainous region with hot springs. But the most important thing is that we were received by the monarchs in their residence. The King is interested in photography. He had technical questions. They themselves suggested that I photograph them.

They liked my photographs, but asked that they not be shown anywhere — private. My younger son Mark helped me, and the communication was wonderful. Despite their sacred status (ordinary people are required to stand with their heads bowed), with us they were very simple and open. They asked questions, were interested in my son’s education. There was a human warmth coming from them, and it was very pleasant.

I was here once about twenty years ago, and then returned this January for this project—three times in total. I like how the majority of people in the country speak English, yet remain deeply attached to their traditions, religion, and national culture. And I’m especially drawn to the personalities of the monarchs. They are easy to talk to. There is a warmth that comes from them, and the population feels it.

They understand the key mechanism of unity—love. And it genuinely comes from them.

EL: Indeed, they are at once down-to-earth and divine. I love what you said in your introduction about how monarchy, religion, and tradition aren’t preserved artifacts but living forces that coexist naturally with innovation and modern life.

This 300-page book is, to quote Her Majesty Queen Jetsun Pema, «a love letter to the kingdom.» As someone who has photographed and traveled Bhutan extensively myself, over the last dozen years, I was truly honored to attend the Royal Book Launch. What was it like for you?

GP: Of course, I am very grateful to them for the opportunity to participate in this wonderful project. It was very beautiful and harmonious. The monarchs radiated joyful openness, and it energized all the guests. It was warm and fun.

EL: You evoke a mystery in your photos. Much like country itself, Bhutan, the last Buddhist kingdom in the world, which is shrouded in mysticism.

There’s the man who holds up the translucent Daphne paper over his face. The dark silhouettes of your subjects, be they crouching in a kitchen or sitting beneath strings of dried chilies in a local restaurant, convey secrecy and anonymity. And there’s both a whimsy and a preciousness—fluttering butter lamps, a singular dry wisteria vine wrapped around a lamp post, a flowing prayer scarf.

It’s like you’ve distilled impermanence itself. Is that inspired by Bhutan, or just your style? You also note “a deep sense of spirituality” in Bhutanese daily life: How does this compare to European culture presently, and how you were raised in the USSR?

GP: My style is my own. But the environment also influences style and inspires new ideas.

If you are familiar with Russian culture, and with Soviet culture as well, you know that it is deeply spiritual and an integral part of European culture. In Bhutan, of course, there are their own traditions, but they are no less spiritual. Many of their leaders have a European education, yet their main objective remains the preservation of their traditions.

EL: You’re known for your extraordinary use of light and color. How do you approach light when you’re photographing?

GP: I pay more attention to light than to color. Light always reflects differently, even of the same objects.

EL: Do you look only for light?

GP: Yes. Without light, there is no image. Everything we see is always light reflected from objects. You’re searching only for the light. If it’s reflected better from other surfaces, you photograph those—and return to the first ones when they begin to reflect light better.

You photograph whatever reflects light best. If you need to capture something specific, you look for the most favorable position—the one where the light falls well. Light dictates everything.

It is equally important to be able to compose the frame. The boundaries of the image define the proportions and create visual tension.

EL: What about Bhutan interests you as a subject?

GP: You can take interesting photos anywhere. A distant country is just an excuse. But it’s not the photography that interests me. It’s the distant country. Thanks to photography, I can get to places I’ve never been, and good photos can be taken anywhere. For me, photography is secondary; it’s an excuse to see the world.

Simple human curiosity propels us on long journeys. And it is also the main source of creativity.

EL: Most of your work has been done on assignment for magazines. Have you had personal projects outside of these commissions?

GP: Unlike other Magnum photographers, I never really had personal projects. Everything I did was through media assignments. But for me, there was no difference. I always photographed for myself—anything that seemed interesting to me personally. There is no such thing as an uninteresting subject; in any situation, one can make a picture that is either interesting or not.

EL: Speaking of your style, and the USSR earlier, you’ve mentioned in other interviews that Soviet film director and screenwriter Andrei Tarkovsky had a profound influence on you – and inspired you to take up photography. Was it one film in particular? I’m not familiar with his work, but I would love to know more about him.

GP: At one time, Tarkovsky’s 1972 film “Solaris” (a Soviet sci-fi drama) made an indelible impression on me. Not everyone could access its depth. Thanks to him, I discovered a new world and, I confess, from that moment I began to feel like an artist. I developed a strong need to create.

EL: Given that you grew up in Moscow, what was it like pursuing photography during the Soviet era? Was it hard to get hold of a camera?

GP: In order to become a photographer, the first requirement is a strong desire. Then you overcome difficulties, even when there are no proper conditions.

The hardest thing was to buy a high-quality Western camera, but even Soviet cameras were not bad. Film was almost free. We bought 300-meter rolls from the factories that produced films for the army (the film in the stores was of poorer quality) and divided them among those who needed it. All developing and printing was done independently. We learned from our mistakes. Some people belonged to photo clubs. I never did. Magnum is the only organization I have ever belonged to.

EL: How many cameras do you use now?

GP: One camera, one lens.

EL: Are you a minimalist?

GP: No, I’m a monarchist (a joke).

But I am a supporter of “mono”: monogamy, monotheism, monologue, for example — therefore one camera and one lens. Minimalism is also close to me.

But the most important thing, of course, is a sense of measure.

I don’t envy wealthy people. I live in sufficiency. Everything extra that you own is a burden. Minimalism is a good vector — simplification. You get rid of everything unnecessary.

And in photography, this works too — nothing superfluous.

EL: You sound like a monk.

GP: Every artist is, to some extent, a monk. Creativity is a search for harmony and never a caprice, like: “I want it this way.” Perhaps: “This is how I see it.” But arbitrariness is excluded. You do not submit to anyone — only to your own muse.

EL: At Magnum, you are also “mono” — the only Russian photographer. How do you understand that singularity? And why, in your view, did Magnum choose you?

GP: I think it’s a coincidence. Photography has no nationality. It doesn’t care what language the photographer speaks. The result depends solely on the author’s involvement in visual culture.

There are Russians who are brilliant artists, directors, and cinematographers with an astonishing visual culture. But unfortunately, they did not choose photography as their profession.

It should be noted that Russian culture, like Protestant culture, is largely literature-centered. Its primary muses prefer narration.

EL: Then your Dostoevsky quote is particularly fitting: “Beauty will save the world.”

***

EL: In your Bhutan introduction, you say, “I’ve always felt that photography is simple. Anyone can be taught not just to look, but to truly see.”

I have to confess something: I’m a writer who wishes she were a photographer. Some have noticed my instinct is to take a photo rather than write down notes.

About a decade ago, I stumbled into a Magnum Photography workshop at my coworking space NeueHouse without even knowing what Magnum was—or how to take a proper photo. I thought I’d learn technical skills; instead, I was told to present 150 photos from my «project» the night before. I scrambled and realized I had over a thousand photos of Bhutan for my guidebook project. Magnum Photographer Peter van Agtmael taught us how to tell a story through sequencing and shapes—as a storyteller, I found this transformative. I was encouraged to publish my own Bhutan photography book but have yet to do so. Now here I am, meeting you, the only Russian photographer in Magnum, in Bhutan of all places, holding a copy of your beautiful book. It feels like a full circle moment—or perhaps even a sign.

I noticed you’ve been advertising an upcoming workshop in Istanbul this May 2026. How do you teach your students to ‘see’? Can anyone join, or must they have an advanced level of understanding?

GP: Yes, I give workshops. No special technical knowledge is required from future participants; the main things is the desire — and a readiness to look in a new way at objects, people, and everything around them.

EL: These days with social media and smart phones, anyone can become a photographer. How has social media changed the field and/or even benefited you? Do you find it a great tool—are smart phones gateway?

GP: The iPhone is a magical tool. Once you master it, it becomes a continuation of yourself, the instrument of your freedom and integration into the world.

EL: Is talent necessary—or can anyone become a good photographer?

GP: I think it is possible. You just need to keep practicing. The desire to learn is much more important than innate talent—whose existence, frankly, I doubt.

EL: So: I’ve been wanting to ask you about your Bukharian Jewish heritage. I understand your father was born in Tashkent, and your mother is Bukharian-Sephardic.

GP: Indeed. My maternal great-great-great grandfather, from the Maimonides dynasty, came from the northern Moroccan city of Tetouan to Bukhara and gave new impetus to Jewish communal life there. One of his descendants, Shimon Hakham (1843-1910), became renowned not only for his poetic works, but also for his public activities. He founded the Bukharian Quarter in Jerusalem. His legacy remains vivid.

My mother told me many interesting stories about them. Unfortunately, however, my parents were not able to integrate me into their culture. I never learned the language – only the cuisine. I cook Bukharian dishes very well.

EL: What rich and tasty heritage! What advice do you have for aspiring Bukharian photographers?

GP: What struck me most in Mongolia were the young photographers who began searching for images of their own country and found almost nothing—except my photographs and a small number by Henri Cartier-Bresson, the renowned photojournalist who traveled widely from the 1950s through the 1970s and produced unique images of the Soviet Union.

In Mongolia, the study of photography led directly to the study of their own history.

You ask what I would wish for young Bukharian photographers. I would advise them not to be carried away by commercial work, but to understand that through photography they preserve their own history.

I managed to document the life of Bukharian Jews in their homeland, from which almost all eventually left, yet—surprisingly—there is little interest in this material. And yet photography remains one of the key witnesses of our very existence.

I would recommend creating a foundation dedicated to studying one’s own history—selflessly, without focusing solely on one’s own relatives—where photography would not be reduced to portraits alone. This could become a remarkable complement to the outstanding museum established by Aron Aronov.

EL: What do you wish for? What’s next?

GP: I’m not a dreamer. I live my life, and life brings wonderful projects.

For me, photography has always been top priority. But now I realize the time has come to work seriously on my invaluable archive.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, I photographed Moscow and Tashkent a great deal – often in very risky situations in the streets. You were seen potentially as a criminal. To quote Cartier-Bresson, “a photographer is part pick-pocket and part tightrope dancer.” I have thousands of negatives that must be reviewed, including rare images of Bukharian Jews. These photographs may cause a real sensation. But they must be selected, taken out of the archive, and scanned. This requires time, assistants, and scanning equipment. I very much hope to find grants or sponsors for this demanding process.

[In his 2021 Bukharian Times interview with Rafael Nektalov, Pinkhassov said, “Today an artist’s identity is defined less by the ability to take a picture than by the ability to select correctly.”]

My ancestors were chroniclers. I continue their work – only in another form. And I sincerely hope I will have time to organize and preserve all this material.

EL: I sincerely hope so, too. Thank you, Gueorgui, for such a fascinating conversation—and for your priceless contributions to world culture.

Follow Gueorgui Pinkhassov on Instagram: @pinkhassov.

Photos from Gueorgui Pinkhassov / Magnum Photos, and Erin Levi

Erin Levi